The 3 Worst Hedge Fund Mistakes of All-Time

From $46 Billion to Zero: The Stories of LTCM, Amaranth, and Archegos

With the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100 both generously in the green for the year, investor sentiment has experienced a notable surge as euphoria makes its way back to the market.

However, it’s important to remember that complacency and overconfidence are an investor’s worst enemy. The market tends to move in cycles, and each cycle doesn’t last forever.

While hedge funds are designed to deliver exceptional returns, history has confirmed that even the most seasoned financial experts are not immune to critical errors.

With that said, let’s take a look at the 3 worst hedge fund mistakes of all time, ranked by the amount of money lost. Each of these mistakes should serve as a cautionary tale into the delicate balance between risk, reward, and leverage.

Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) - $4.6 Billion Loss

“Long-Term had the equivalent of Michael Jordan and Muhammad Ali on the same team.”

Roger Lowenstein, author of When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management

While the $4.6 billion collapse of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) comes in at #3 on the list, the ripples of its downfall carried the greatest potential to trigger a systemic collapse of the entire financial system.

Founded in 1994 by several partners with decorated financial backgrounds and led by famed Salomon Brothers bond trader John Meriwether, LTCM seemed destined for success with such a star-studded cast. Its board even included Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton, two of the three economists behind the Black-Scholes model. The pair went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1997 for their options pricing formula. Put simply, LTCM was the top dog on Wall Street from the moment of its inception.

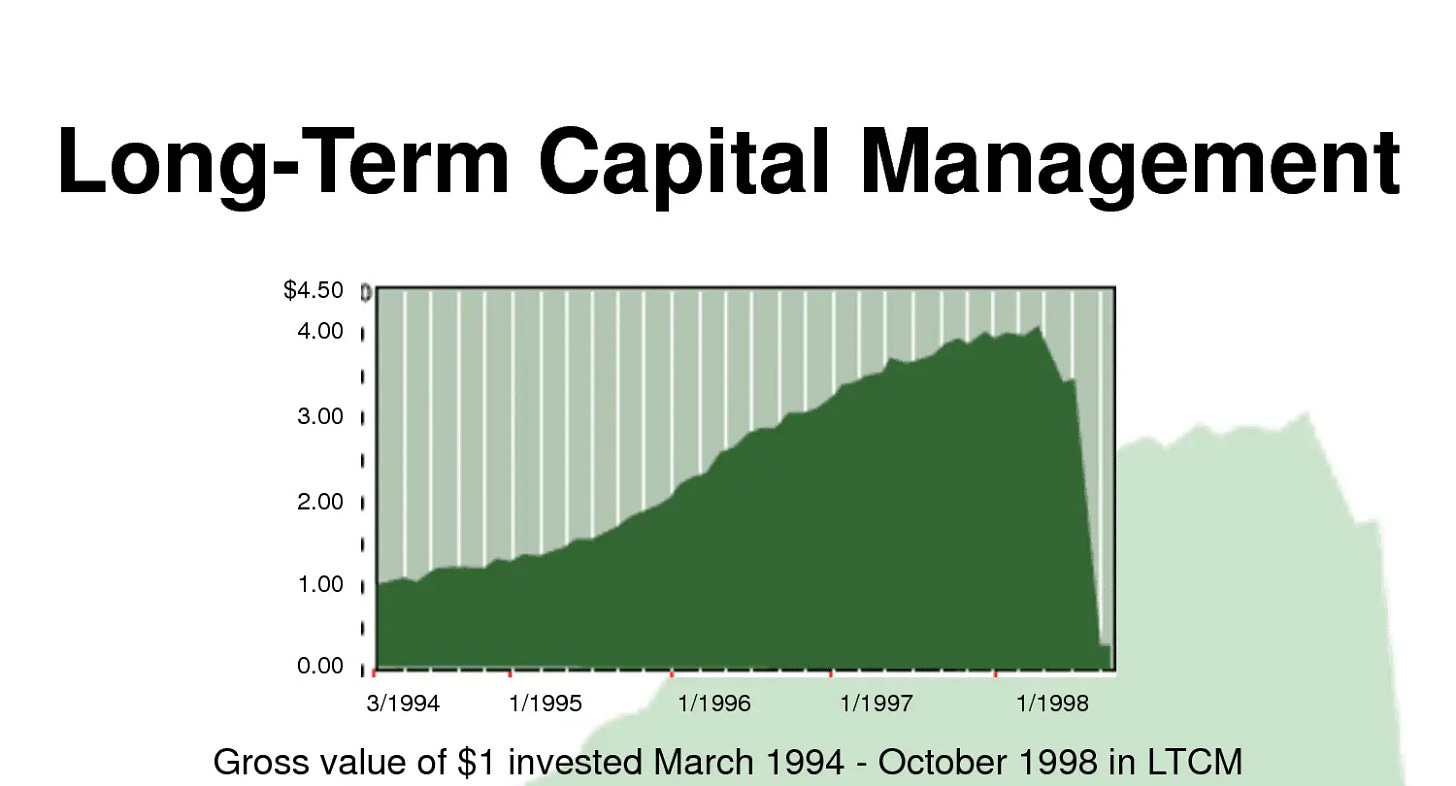

With seed capital of $1.3 billion, equivalent to $2.74 billion in today’s dollars, LTCM took on a highly leveraged approach using complex quantitative models. Its main strategy was bond convergence trading, which involves finding a pair of improperly priced bonds with a predictable spread. LTCM would then bet that the bond prices would converge by taking long and short positions in the bonds. These spreads were often minuscule, so leverage was needed to amplify the gains. LTCM didn’t just limit itself to the U.S. market; its fixed income activities also found its way into Europe, Asia, and South America.

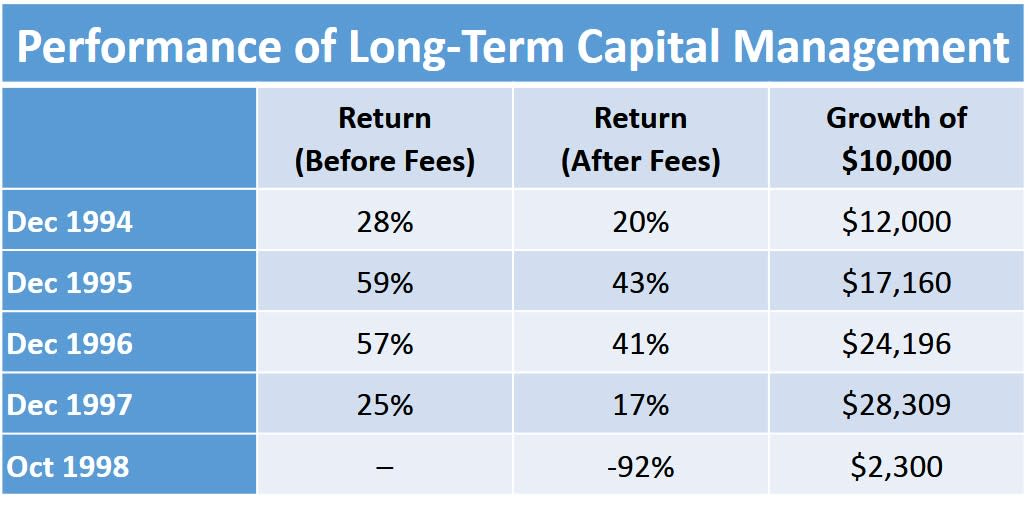

The strategy was a raging success and helped contribute to 43% gain in 1995 followed by a 41% gain in 1996. These returns accounted for a 27% management and performance fee.

However, other traders caught on to the bond pricing anomalies, diminishing the value of the strategy. LTCM returned 17% net of fees in 1997, marking the first time it had ever underperformed the S&P 500. Its AUM had climbed to $7 billion, making it one of the largest hedge funds in the world. At the end of the year, LTCM returned $2.7 billion back to its investors because “investment opportunities were not large and attractive enough.”

At the same time, LTCM’s open positions weren’t reduced in proportion with the capital returned, meaning that its leverage increased. The hedge fund had also ventured into new, unfamiliar areas of the market, such as swaps, options, foreign currencies, and emerging markets like Russia. These two factors would ultimately lead to its demise.

LTCM’s net asset value (NAV) totaled $4.7 billion at the beginning of 1998, while its leveraged portfolio had a value of $129 billion, equating to a leverage ratio of 27.4-to-1. Its derivatives, mostly interest rate instruments, had a notional value of $1.25 trillion.

In July, Salomon Brothers announced the closure and liquidation of its arbitrage arm. LTCM took a 10% loss that month as Meriwether and co. had utilized similar arbitrage strategies.

The following month, Russia's default on its domestic currency bonds sparked a frantic selloff of riskier positions as capital rushed to safer ground. Investors piled into U.S. Treasury bonds, sending interest rates lower. LTCM happened to be on the other side of both of these trades, further intensifying the rate of its margin calls.

By late September, the hedge fund’s NAV had fallen to $400 million compared to its portfolio value of over $100 billion, implying a leverage ratio of over 250-to-1. That posed a massive issue for its lenders, as well as for the markets underlying those positions.

On Sept. 23, Warren Buffett, Goldman Sachs, and AIG proposed an offer to buy out LTCM’s partners for $250 million while providing the fund with $3.75 billion and absorbing it into Goldman’s trading division. Buffett gave the partners less than an hour to decide, which caused the deal to lapse.

With the impending threat of a global financial collapse due to LTCM's colossal bets and extensive reliance on lenders, the Federal Reserve decided to take matters into its own hands. The Fed organized a $3.6 billion bailout funded by 14 major banks, which included Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and Barclays. The banks also received a 90% stake in LTCM.

At the end of the day, LTCM’s partners saw their combined $1.9 billion of capital within the fund completely wiped out. Surprisingly, Meriwether wasted no time and formed a new hedge fund, JWM Partners, with money from legacy LTCM partners and investors. Following a 44% decline during the Great Recession, JWM was permanently shuttered.

Amaranth Advisors - $6 Billion Loss

2005 was an exceptional year for Amaranth Advisors, a hedge fund with $9.2 billion in AUM at its peak. Its star energy trader, Brian Hunter, had placed bullish bets on natural gas prices before the tragic events of Hurricane Katrina and Rita wreaked havoc across several states, destroying hundreds of oil pipelines and drilling platforms and sending up the price of natural gas in the process. Amaranth ended the year up by about 18% compared to the S&P 500’s 4.91% return. Hunter’s trades had been responsible for 80% of the hedge fund’s profits.

That set the stage for a confident Hunter, who was rumored to have taken home a bonus check worth between $75 to $100 million for his performance. Amaranth’s investors, including Goldman Sachs and the San Diego County Employees Retirement Association, were extremely pleased as well.

Little did they know that it would all come crashing down the following year. In mid to late 2006, Hunter took on a series of trades worth $5.7 billion using 5-to-1 leverage. One of these trades was that the March and April spreads of 2007 and 2008 natural gas futures would increase. Hunter placed the long-winter, short-summer bet with the belief that the March contract prices would rise, as it is the last month of winter, while the April contract prices would fall as temperatures begin to rise.

In a win for humanity, Mother Nature produced a calm 2006 hurricane season that didn’t interfere with natural gas production, leaving inventories plentiful. That came despite a cautious prediction from the U.S. Hurricane Centre, which helped spur an increase in inventory in preparation.

At the end of the August, the spread between the April and March 2007 contracts was $2.49. By the end of September, the spread had plunged to 58 cents.

Amaranth lost $560 million on Sept. 14, its worst ever one-day loss. Selling out of its losing trades was a difficult task due to the sheer size and declining natural gas prices, which resulted in the fund transferring its energy portfolio to JP Morgan and Citadel in order to decrease its leverage and avoid defaulting with its brokers.

“J.P. Morgan's bankers and Citadel's portfolio managers first raced to estimate the value of Amaranth's investments -- a difficult task, given the illiquidity of some of the markets the hedge fund focused on… Then they spent a furious day persuading those two dozen or so counterparties to rip up their derivative-trade contracts with the struggling hedge fund and sign agreements with the new owners, and then transfer the portfolio to them. Along the way, J.P. Morgan and Citadel hashed out their own agreement to share the deal's risk and potential upside.”

-WSJ

A week later, Amaranth disclosed a loss of about $6 billion and a 65% decline in September. The liquidation process began the next month.

Later on, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) charged Hunter with market manipulation, while the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) charged him with attempting to manipulate the prices of natural gas futures. The FERC fined Hunter $30 million, to which he appealed and won due to the commission not having jurisdiction in the futures market. In 2014, he settled with the CFTC for $750,000 and limitations on future trading.

Archegos Capital Management - $36 Billion Loss

Many are familiar with the downfall of Archegos Capital and Bill Hwang due to its recency. However, the scale and speed at which Hwang incinerated tens of billions of dollars was absolutely unprecedented, resulting in allegations of deception from Wall Street’s largest investment banks and over $100 billion of market cap loss for several companies.

Before Archegos, Hwang worked under Julian Robertson’s wing at Tiger Management. After Tiger Management closed down in 2000, Hwang founded Tiger Asia, which received $25 million in seed capital from Robertson. Tiger Asia grew its AUM to over $5 billion at one point but then sustained heavy losses during the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis. Afterwards, the fund ran into serious legal trouble involving insider trading.

“The SEC alleges that Sung Kook "Bill" Hwang, the founder and portfolio manager of Tiger Asia Management and Tiger Asia Partners, committed insider trading by short selling three Chinese bank stocks based on confidential information they received in private placement offerings. Hwang and his advisory firms then covered the short positions with private placement shares purchased at a significant discount to the stocks' market price.”

-SEC, 2012

Hwang and Tiger Asia ended up settling with the SEC for $44 million. Tiger Asia pled guilty to wire fraud and agreed to forfeit $16 million in illegal gains while taking on one year of probation.

With a permanent stain in its reputation, Hwang made the decision to shut down Tiger Asia. From the ashes rose Archegos Capital Management, a family office fully and solely funded by Hwang. Its initial capital tallied between $100 and $200 million, according to varying sources.

Archegos, the ancient Greek word for “leader,” was a success early on, led by its bets on technology companies such as Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Netflix. By March 2020, its AUM had grown to $1.5 billion.

At some point in the years before Archegos’ collapse, Hwang’s investment strategy took a sudden pivot from opportunistic tech stocks to much riskier Chinese and media stocks. Along with the change came a thirst for more leverage.

Beginning in mid-2020, Hwang’s bankers saw their positions in stocks like ViacomCBS, Discovery, Baidu, and GSX Techedu increase dramatically. This was attributable to Hwang and his use of leverage and total return swaps.

Total return swaps provide an investor with exposure to the returns of a stock without the investor having to actually hold the stock. Hwang transacted the swaps with several different banks. He used these banks to buy swaps on the same stock in order to avoid having to file a Schedule 13G once his stake in a company surpassed the 5% threshold. Archegos was also exempt from filing a quarterly Form 13F due to its status as a family office.

No one outside of Archegos knew that Hwang was amassing significant stakes in these companies and driving up the prices simultaneously, collecting billions along the way.

Archegos’ AUM swelled to $36 billion by March 2021, a year-over-year increase of 2,300%. Its overall market exposure including leverage totaled $160 billion.

“All the alumni, we keep in touch and talk to each other,” a Tiger Cub told Forbes. “It was well known within Tiger that Bill was worth more than Julian. He had multiple 100% years.”

Then, the first domino fell. On March 22, ViacomCBS announced a $3 billion stock and debt offering, sending its shares lower by 32% over the next two trading days. Hwang doubled down but the stock continued to plummet, sparking a margin call. The problem was that Hwang didn’t have any money left to satisfy it, which forced him to liquidate his other massive positions before defaulting, causing a steep plunge in prices as banks rushed to sell out.

Some banks were able to unload their swap positions with minimal damage while others weren’t so lucky. Credit Suisse suffered the most damage with a loss of $5.5 billion, followed by Nomura with $2.9 billion. In total, the situation cost seven banks $10.3 billion. The resulting rush for the exit also led to over $100 billion of market cap evisceration.

In the following weeks, Hwang received a slew of criminal charges including market manipulation, securities fraud, wire fraud, and racketeering. His fraud charges trial is set for May 6.

The stories of LTCM, Amaranth, and Archegos serve as valuable case studies, highlighting the dangers of unchecked ambition and excessive leverage. Beyond the billions lost, these financial disasters underscore the importance of risk management, proper due diligence, and accountability.

Hedge Vision - Institutional Insights

Thanks for reading!

📖 Join the conversation on Substack Chat

🕊️ Get real-time insights on X/Twitter: @HedgeVision

📧 Old school is cool too: HedgeVisions@gmail.com