Ken Griffin, Citadel, and the $35 Billion Year

Citadel's dominant streak led to a record-breaking year

“If you make $100 million here and someone down the street makes $400 million, you'd better be thinking about why you didn't make $500 million.”

Last year, Ken Griffin’s Citadel pulled in $28 billion of revenue, of which clients were charged around $12 billion in performance and management fees. Since inception, the hedge fund has generated $65.9 billion in net gains.

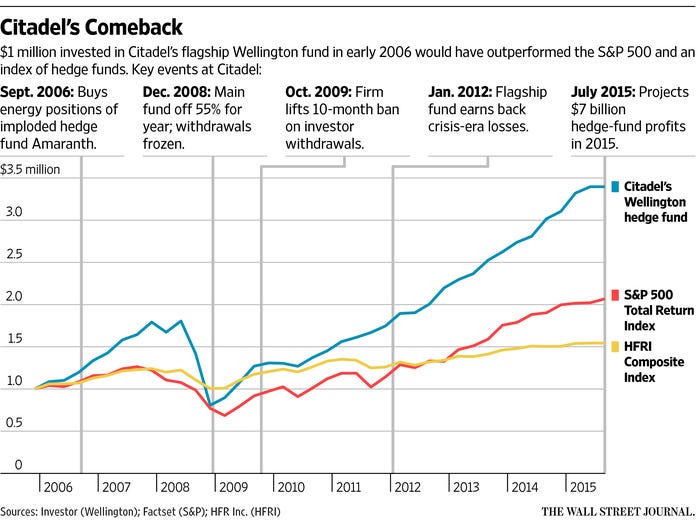

All four of Citadel’s main funds managed to outperform the S&P 500 by a wide margin, led by the flagship Wellington Fund:

Wellington Fund: 38.10%

Global Fixed Income Fund: 32.58%

Tactical Trading Fund: 26.49%

Equities Fund: 21.40%

S&P 500: -19.44%

Based on the HFRI 500 Fund Weighted Composite Index, the average hedge fund lost 4.25% in 2022, representing the largest decline since -4.75% in 2018.

Citadel Securities (CS), a market maker that operates separately from Citadel, raked in revenue of $7.5 billion. CS has now reported 12 consecutive quarters of at least $1 billion in revenue. That’s been partly driven by the prevalence and popularity of options trading among retail investors in recent years.

According to LCH Investments, Citadel’s net return of $16 billion for 2022 cements Griffin as having the largest annual return for a hedge fund manager ever. Griffin’s return even managed to outpace John Paulson’s $15 billion gain in 2007 from betting against subprime mortgages. The outsized gains led to Citadel announcing at the end of the year that it would return $7 billion in profits to its clients in an effort to remain lean.

Since Citadel’s inception in 1990, Griffin has remained deliberately vague on the details of the investment strategies employed by the fund. However, its known that Citadel trades in a variety of asset classes, such as bonds, commodities, options, currency, and equities, using algorithms, risk arbitrage and event-driven strategies, and leverage. It’s been reported that the fund employs leverage between 300% and 700%.

Let’s not forget about Citadel and CS’s controversial involvement in high-frequency trading (HFT). Last month, the firm was fined $9.66 million by South Korea’s Financial Services Commission for the practice. Per Reuters:

“The Financial Services Commission (FSC) said in a statement released on Thursday the firm had distorted stock prices with artificial factors, such as orders on the condition of "immediate or cancel" and by filling gaps in bid prices. The firm carried out such trading on an average of 1,422 stocks per day from Oct. 2017 to May 2018, totaling more than 500 billion won worth of trades, according to the statement. The Commission said it was the first time it had imposed fines on such high-frequency trading on the South Korean stock market, which has a high proportion of retail investors and little competition among algorithmic traders.”

Citadel denied the claims and noted that it would seek to appeal the decision.

Many of the securities that Citadel trades in are not required to be disclosed through a quarterly 13F filing. The fund had $62.3 billion in AUM as of the beginning of this year.

Its top 13F positions as of December 31, 2022 were all options:

Leverage is your best friend if you’re right and your worst enemy if you’re wrong. With that said, Citadel has passed the test of time with flying colors to provide stellar returns. $1 million invested into the Wellington Fund at its inception in 1990 would be worth $328 million today, handily beating out the S&P 500’s comparative value of $22 million.

Griffin cites a collaborative and tight-knit employee base as a major reason for Citadel’s longevity. Even today, the firm has distanced itself from the trend of working from home and requires all employees in the office. In 2015, it was awarded the Top 10 Great Workplaces in Financial Services award by the Great Places to Work Institute.

On the other hand, Citadel gained the nickname of “Chicago’s revolving door” in the 2000s for its high employee turnover and rigorous work standards. A former manager who spoke on the condition of anonymity said:

“Citadel can be a real sweatshop. You have to be incredibly energetic, willing to give your life up to work there. The money is good - it's a hedge fund - but that doesn't seem to do much for employee retention.”

In an email to Griffin in 2005, Third Point’s Dan Loeb said:

“I find the disconnect between your self-proclaimed 'good to great, Jim Collins-esque' organization and the reality of the gulag you created quite laughable. You are surrounded by sycophants, but even you must know that the people who work for you despise and resent you. I assume you know this because I have read the employment agreements that you make people sign.”

Today, job message boards still place caution on the long hours required by Citadel. But is anyone surprised?

Ken Griffin - President of the Math Club

"Ken wasn't your typical 17-year-old who'd hang out at the movies. His friends tended to be older. He knew where he wanted to go. He was always coming up with ideas."

-Early friend of Griffin

To truly understand Griffin and the empire that he built, we’ll have to take a dive into his early years.

Griffin made local headlines at age 17 when he was featured in South Florida’s Sun Sentinel publication. Sun Sentinel lauded Griffin and 3 other Boca Raton Community high school students for their dedicated work ethic on the computer programming team. While other kids were playing sports and hanging out after classes, Griffin and his team were hard at work in the lab practicing for the next district programming competition.

At the time, Griffin was also the President of the Math Club and ran EDCOM, a small software distribution company that mailed educational software to college professors. When communicating with suppliers and buyers, Griffin always made sure to keep hush on his age.

"Do you think anyone would trust their product line to a 17-year-old kid?

-Ken Griffin, 1986

Griffin’s early interest in education resulted in multiple business ventures. With assistance from a guidance counselor, he was able to develop four educational programs. Two of these programs were approved for use in schools after winning the National Education Association seal of approval.

The earliest account of Griffin’s interest in the stock market dates back to 1986 when he read a bearish Forbes piece on Home Shopping Network. That subsequently inspired him to purchase put options on the company, which rewarded him with a $5,000 profit. At the same time, Griffin was vexed by the high broker fees, a thought that remained with him in his early years at Harvard University.

Harvard Years

After high school, Griffin headed up north by enrolling in Harvard as an economics major. By October of 1987, Griffin had founded his first hedge fund, G & S Capital, with the backing of Saul Golkin, Rush Simonson, and his mother and grandmother. Back then, the industry was much less regulated than when compared to today, making the process of starting a fund easier.

“He was already very intense and a savvy businessman as a freshman.”

-George Juang, Freshman year roommate

In his dorm room, Griffin faced a major problem. The only way to get timely stock quotes was via a satellite dish, which his building was not equipped with.

In addition, university policies stipulated that students were not allowed to operate businesses on campus, threatening the very existence of G & S. Griffin responded by hosting a successful lobbying campaign, which resulted in the hedge fund being classified as an off-campus activity. Harvard also miraculously allowed Griffin to install his own satellite dish on the dorm building.

Griffin jumped out of the gates with an AUM of $265,000 and a net short position using a convertible arbitrage strategy. That’s worth about $682,000 today when adjusted for inflation. Whether it was luck or timing, G & S made it just in time for the monumental 1987 crash, otherwise known as Black Monday. The Dow Jones plummeted by 22.6% on October 19, benefitting Griffin’s young fund in the process.

Following an early graduation in 1989, Griffin relocated to Chicago to work for Glenwood Capital and founder Frank Meyer. In 2014, Griffin retraced his steps by issuing a record-breaking $150 million donation to his alma mater.

Citadel - A Hedge Fund Powerhouse is Born

Meyer was well aware of Griffin’s accolades and provided him with $1 million in initial capital. Griffin responded by returning around 70% in just one year for Glenwood using his reliable convertible arbitrage strategy, earning Meyer’s trust along the way.

In 1990, Meyer helped Griffin found Wellington Partners, which was later renamed to Citadel, with an initial AUM of $18 million. Griffin continued his hot streak and returned 43% in 1991 and 40% in 1992 trading U.S. and Japanese convertibles.

“It was a global arbitrage shop run by a 22-year-old.”

-David Bunning, Citadel’s sixth employee

By 1994, Citadel had expanded to 60 traders and analysts. However, the bond market witnessed a historic decline that year, causing several hedge fund closures across the board. In a panic, Citadel’s clients withdrew about a third of their capital, resulting in a 4.3% decline for the fund. That marked Citadel’s first down year.

Still, Griffin didn’t let one subpar year get the best of him. The firm breezed through the dot-com bubble and the subsequent market crash, rewarding clients with positive returns from 1995 through 2007. At the same time, the collapse of funds and companies throughout the industry allowed Citadel to take advantage of laid-off talent.

By 2007, Citadel had $16 billion in AUM.

Everything was going according to plan until the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. Citadel was hit by an $8 billion loss after employing a 4:1 leverage ratio, and its two largest funds finished the year down by 55%. The poor returns were exasperated by Griffin incorrectly timing the bottom, a global credit and regulatory freeze that stymied convertible-bond arbitrage strategies, and margin calls.

Investor fear elevated to a level so high that Griffin had to resort to suspending redemptions.

“One of the most difficult decisions that I ever made was suspending redemptions in 2008. I knew it had to be done to protect our balance sheet, preserve our investors’ capital and to maximize short-term performance. My focus was on the long-term, and by the end of 2009 we had not only revoked the suspension but also rewarded our patient investors with a 62 percent net rate of return.”

On September 19, the SEC announced a temporary ban on the short-selling of 900 stocks, causing a detrimental effect to Citadel’s convertible arbitrage strategy. Griffin had allegedly contacted SEC Chairman Christopher Cox beforehand to plead with him to not follow through with the ban.

By the end of September, Citadel was down by 20%. Griffin described that month as the "single worst month, by far, in the firm's history. Our performance reflected extraordinary market conditions that I did not fully anticipate, combined with regulatory changes driven more by populism than policy."

In October, Standard & Poor downgraded Citadel’s bonds to negative from stable. The rating was downgraded again the following month.

At one point during the year, the firm was losing “hundreds of millions of dollars each week." On top of that, rumors circulated within the industry that Citadel had approached the Fed for financial assistance. Griffin later disproved these rumors after holding a 12 minute conference call, disclosing a 30% cash position and an $8 billion line of credit.

Still, the resilient Griffin bounced back in a timely manner, setting up an investment banking operation in the same year as the the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. The unit was eventually put on sale in 2011 due to a lack of deals and high employee turnover.

In a December 2008 interview, Griffin stated that Citadel would simplify its strategy and primarily focus on long/short equities. Citadel also laid off about 20 employees and created new single-strategy funds.

By 2012, Citadel’s Wellington and Kensington funds had both crossed their high water marks, allowing them to resume performance and management fees.

Accusations of Market Manipulation

CS caused an uproar among the r/WallStreetBets crowd in January of 2021 following the gravity-defying events of GME 0.00%↑. The internet community accused CS of purposely restricting the trading of GME in an attempt to deflate the price. In a written testimony to the House Financial Services Committee, Griffin stated that his firm “had no role in Robinhood’s decision to limit trading in GameStop or any other of the ‘meme’ stocks.”

Robinhood testified that it placed the halts on certain stocks due to a $3 billion margin call from the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), which was corroborated by the agency.

Other accusatory comments flood the Reddit forum, accusing Citadel of illegally conspiring with CS by sharing order flow and front-running trades. Griffin has always maintained that Citadel and CS operate as separate entities, which is heavily regulated by law.

On the contrary, there are several instances in which Citadel and CS have been alleged of market manipulation and wrongdoing:

1999: Accusations of mismarking positions in order to inflate gains after returning 45% in a year. Citadel responded by hiring an independent auditor, who confirmed no signs of wrongdoing.

2006: G & S Capital Partner Rush Simonson sues Citadel and Griffin, alleging him of “fraud, breach of a partnership agreement and misappropriation of trade secrets involving investment partnerships the two worked on while Griffin was in college in the late 1980s.” The lawsuit is later dropped.

2014: A unit of Citadel is fined $800,000 for failing to prevent the transmission of erroneous orders from retail clients to exchanges.

2017: CS settles with the SEC for $22.6 million for not giving retail customer orders from other brokerage firms the best possible market price, despite saying that it did.

2018: CS, along with broker-dealers Natixis Securities and MUFG Securities, are fined $6 million for inaccurate and missing data during the blue sheet submission process, order execution times that failed to adjust for time zone changes, and more. Citadel paid the highest penalty of $3.5 million.

2020: CS settles with the SEC for $700,000 for trading ahead of client OTC orders between 2012 and 2014.

2020: CS settles with the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) for $97 million due to vague trading irregularities likely related to HFT and short selling.

2021: Robinhood debacle involving the trading restriction of meme stocks. In November, a U.S. District Court dismissed a class action lawsuit alleging collusion between Robinhood and Citadel.

2021: CS fined $275,000 for improperly reporting about half a million Treasury transactions between 2017 and 2019.

2022: Northwest Therapeutics (OTCMKTS:NWBO) files a lawsuit alleging CS and other market makers of spoofing.

2023: CS fined $9.66 million by South Korea’s Financial Services Commission for HFT violations.

There’s no doubt that Griffin has built a diamond-plated powerhouse in Citadel and CS. Although he’s fielded countless accusations throughout the years, Griffin continues to outperform in an exceptional and unrelenting manner. The thick veil behind the two firm’s strategies and Griffin’s involvement in publicized events has captivated audiences throughout the years, etching him a permanent spot in the Wall Street history books.

"I try to surround myself with people who disagree with me. Successful people tend to be very overconfident about what they know, and it leads to tragic mistakes. That will not be the final chapter in my career.”

Hedge Vision - Institutional Insights

Please don’t hesitate to send me topic recommendations, suggestions, or general questions. You can contact me by email: HedgeVisions@gmail.com, or by Twitter messages @HedgeVision

great comprehensive take, thank you!